As a cross country coach for more than a decade, I continue to learn lessons that help my own running. High school runners may be less than half my age, but they face similar challenges, and the controlled setting lets me try out new tactics and observe trends over the course of a season and a student’s career. Here are a few of the top cross country training tips I’ve learned that we all can apply as we “go back to school” this fall.

As a cross country coach for more than a decade, I continue to learn lessons that help my own running. High school runners may be less than half my age, but they face similar challenges, and the controlled setting lets me try out new tactics and observe trends over the course of a season and a student’s career. Here are a few of the top cross country training tips I’ve learned that we all can apply as we “go back to school” this fall.

1) Fresh Legs Are Fast

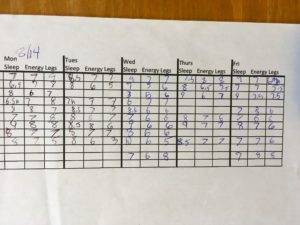

For several years, I’ve asked runners to fill out a self-evaluation recovery form at the beginning of every practice. Each day they report how many hours they slept and rank their overall energy level and the condition of their legs on a scale of 1 to 10. It didn’t take long to notice the correlation between leg freshness and the quality of workouts. Runners can only run fast and strong if they are recovered, which is different for each runner and for each type of workout—and doesn’t always correlate with the predicted days off or what may seem to be an acceptable volume of “easy day” miles. Putting an athlete through a workout with still-stale legs erodes confidence and usually ends up making them staler—and slower—come race day.

What this has pushed us towards are more very-easy days and a couple well-rested days when we run faster, harder and longer than we used to. Which, of course, is the pattern top coaches are constantly recommending: training should regularly range over a large variation in paces and efforts, rather than the common pattern of doing roughly the same thing every day.

As adults, many of us get caught into the trap of worrying more about daily miles and getting in our scheduled workouts than making sure we are rested and then hitting key workouts at full intensity. We’d enjoy hard workouts more—and get more out of them—if we paid attention and took down days when we needed to rather than perpetuating a continual level of fatigue and half-recovery.

2) Injuries Are Optional

Many runners seem to believe that injuries are a nearly-inevitable part of training hard toward a goal. As a coach of a small team that often has barely enough runners to field a varsity, I’ve not been able to waste any runners to overtraining and injury. And we haven’t: we’ve had only a couple runners who needed to sit out a meet due to injury over several years. Those exceptions have all been either runners who showed up at practice without doing summer conditioning, a few who had unlucky pulls or twists during a hard workout or race, or a runner who did more-than-recommended workouts on the weekends.

I’ll admit it is possible that a few gifted runners have been undertrained, but I’ll take a healthy team heading into the championship season over a few survivors who are riding the knife’s edge. Elite runners I’ve met, who have stayed competitive for a lifetime, emphasize that they learned early to monitor their bodies in order to run well week after week, year after year. It is that that consistency that took them to higher peaks more than any concentrated, over-the-top, single training season.

The keys to staying off the injured list are well known: gradual, consistent progression in training load, both volume and intensity, and regular maintenance of essential strengths and flexibility. Our high school runners start at the beginning of June to train for a goal 5K at the end of October. As adult runners, just thinking about our running in this type of season, and using a block of early-season training time to get ready to train, will go a long way toward eliminating injuries.

3) Running Tall Requires Work

3) Running Tall Requires Work

I used to believe that the way to a more efficient form was simply to run more—but that was in the day when, any time children were free they were out running through the woods, climbing trees, playing pick-up ball games. According to a large U.S. study conducted in 2003-2004, children aged 12–15 spent nearly 8 hours a day being sedentary. Observational evidence suggests that number has increased in the ensuing years.* Therefore, todays youth tend to be as compromised as adults, with tight hips, weak glutes and core, fragile feet, rounded shoulders and poor posture and balance.

When I started coaching, I spent time trying to correct runners’ form with cues, drills and forcing faster cadence. Over the years I’ve learned that experts agree that runners’ bodies know better how they should stride than I do as a coach, and improvements come not by cueing a “perfect” form but by building better systems. We now spend our time improving range of motion with hip stretches, building key strengths with exercises like squats, bridges and side leg-lifts, and developing posture and balance with drills and one-legged exercises and games. Then we shake things up by running on rough terrain and doing barefoot striders to help bodies find their best stride with their improved systems.

I find that even 15-year-olds need this work daily to counteract their hours of sitting and hunching. As an adult with far more sedentary years, I need even more. While I do a few exercises every morning of the year while making my daily coffee, I find that when I’m in season, and doing all the exercises, drills and barefoot running with the kids, my stride is lighter, more powerful, and less painful. I’m learning that a natural stride is not something learned or achieved, but a continual work in progress like the rest of our fitness.

4) Everything Matters

4) Everything Matters

Observing our recovery sheets over the years revealed another discovery: while leg freshness tends to correlate closely to the intensity of previous days’ workloads, overall energy seems to vary randomly. On an early-season Monday afternoon this fall, for example, all the runners reported low energy, even though they had just taken the weekend off and all had gotten in a good night’s sleep. Asking them about it revealed the culprit: It was the first full day of school, and the change in routine and new stresses had them feeling drained.

What we’ve learned is that everything matters when it comes to athletes feeling recovered and able to handle hard work. Their reported energy levels often are more affected by a big test, a dance, the school play, or a family conflict than by yesterday’s hard workout. In the days leading to a key race, we now talk as much about minimizing other stresses and distractions as about physical rest.

Adult runners are no different. We are not machines, there is no mind/body divide; we are whole humans and everything in our lives affects our ability to perform and to adapt to training stress. Just like high school runners, we need to reduce other stresses during times when we want to run our best, and we need to make allowances for unavoidable life pressures as we create our training and racing plans and as we adapt our best workout each day.

* https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3527832/

__________________________

The Whole Athlete is a monthly running series written by Jonathan Beverly and brought to you by Topo Athletic. We aim to deliver advice that serves the whole athlete, from training and recovery to nutrition and psychology.

Jonathan Beverly is author of Your Best Stride and Run Strong, Stay Hungry. A lifetime runner, his passion is to help others experience the joy of training, competing and being fit and fully alive.

Jonathan Beverly is author of Your Best Stride and Run Strong, Stay Hungry. A lifetime runner, his passion is to help others experience the joy of training, competing and being fit and fully alive.

He served as editor of Running Times from 2000-2015 and has coached runners of all ages and disciplines.

Greetings! Very helpful advice within this post! It’s the little

changes that produce the most important changes. Many

thanks for sharing!